I’ve heard it many, many times:

“You are supposed to wash it?”

“I don’t want to ruin it by washing it.”

“My coat doesn’t keep me dry anymore but I have never washed it”.

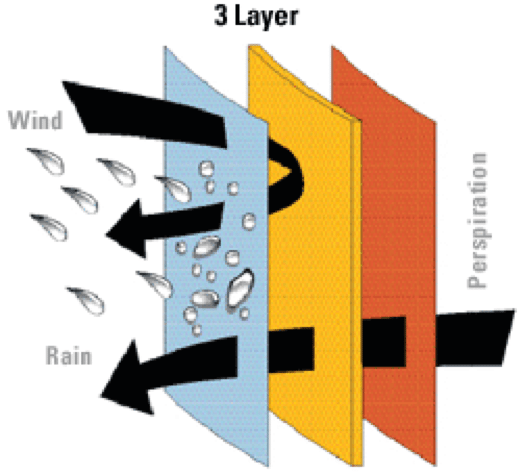

Really? You think that sweat, grime, and dirt is GOOD for your clothing? Enough of my ranting. Keeping your investment clean a critical component to making it last. Salt, grime, sweat, and body oils reduce the function of the properties that make your clothing special. Surface dirt affects the DWR (Durable Water Repellency), and the rest of it can clog moisture movement.

The days of Ivory Soap Flakes are long gone. Now there are excellent products out on the market that make keeping your clothing clean and functioning easy. The two main product lines are Nikwax and Granger’s. They both make a full line of environmentally friendly and easy to use laundry products specifically formulated for different types of fibers. You will want to read the label to be sure you are matching the right product for your particular item. There are down washes, soft shell washes, fleece washes and washes for hardshells and even ropes.

For hard shells, you will have the choice of a one-step or two step process. The steps are cleaning your item, and refreshing the DWR. The two-step process is washing first, then waterproofing. I have not yet tried the newer one step products. If you opt for the two step process for your hardshell, I suggest using the spray-on for the #2 step, and not the wash-in. The reason to choose the spray on is that that you will not be coating the lining of your item with DWR, which, if coated, can make it feel funky and possibly reduce the effectiveness. Whether you go one-step or two, it is easy: just follow the directions on the bottle.

I wash all our shell clothing at the end of the ski season, and then again mid-way through. One additional thing you can do with your shells is to toss them in a low dryer for a few minutes without washing them. The heat reactivates the DWR, which is the treatment that makes moisture bead up on the outside. WARNING: use a low dryer, not hot. Hot dryers are the enemy. The DWR does lose effectiveness after time, due to environmental conditions, so you will want to renew it using the above instructions to wash and renew. You know if moisture is not beading up that it’s time.

You can do down items with down-specific products. There are two critical elements. The first is to only use a non-agitator washer like a front loader, and the second is drying your down. The drying is the critical element with down as it can take hours of air dry and breaking up clumps by hand to get your item fully dry.

A few other tips:

- HOT dryers are the enemy. Avoid them at all costs. You can melt things and cause seam seal tape to delaminate.

- You can use “Shout” and similar laundry helpers to get grime and grease out. You can even use Simple Green or Dawn for things like chair lift grease.

- Do not spend extra money for sportswear oriented laundry products. Just use your regular stuff with some OxiClean.

- For handwashing, just use baby shampoo instead of Woolite. Milder, and cheaper.